Share this page:

One of the most interesting scientific museums in Australia is in the small town of Canowindra in the central west of NSW.

It is the Age of Fishes Museum that displays many hundreds of freshwater fish fossils that were unearthed in the Canowindra area. The fossils date from the Devonian Era of geological history, an era before dinosaurs, before tetrapods (four legged animals) and before man.

The famous rock slab of fish fossils found near Canowindra in 1955.

The Canowindra grossi can be seen in the lower centre of the slab (it coloured blue on the accompanying diagram).

This slab is now back in Canowindra and on display in the Age of Fishes Museum.

(Photo: Dr Anne Dollin.)

At the time the fish of the Devonian Era lived (the fish that have now come down to us as these fossils) there were great rivers in what is now known as the Central West of New South Wales and they were teeming with armored fish (fish encased in armor plating), fish with lungs (fish that breathed air a bit like us, not via gills) and predator fish with jaws with powerful jaws and sharp teeth (a bit like crocodiles).

The entrance to The Museum of Fishes

A Museum that Almost Did Not Happen

The discovery of Canowindra's fossils has actually occurred three times – and they were forgotten twice (fortunately not three times!).

In 1955 a road worker who was grading a spot about 10 km west of Canowindra (on the Gooloogong Road between Canowindra and Gooloogong) unearthed a large rock slab with unusual impressions on it. He pushed the slab to the fence line at the side of the road, where it was to lie forgotten.

Later in the same year a local Canowindra apiarist, Bill (William) Simpson, came across the slab and thought that the impressions might be fossils. He contacted Dr Harold Fletcher, the then Curator of Palaeontology at Sydney's Australian Museum. Fletcher came to Canowindra with Dr Ted Rayner of the NSW Mines Department during a tour they were making of the NSW countryside in 1955. Fletcher confirmed that the slab did indeed contain fossils – fish fossils and, in fact, not just a few but hundreds of them -- and had it transported to the Australian Museum where from 1966 it was put on permanent display.

But the site where the slab had been found was not researched and further explored and with the realignment of roads in the area, the exact location of the discovery of the slab was forgotten.

It was only with the appointment of the Scottish fish fossil expert Dr Alex Ritchie to the Australian Museum that interest in the Canowindra's fossils was rekindled. Ritchie visited the Canowindra on a number of occasions in the period from 1973 until 1990 and tried to locate where the fossils had been found.

All to no avail until in September 1992 when he gave a talk, "Great Canowindra Fish Fossils", to the local service club, Canowindra Rotary. Suddenly a wide range of local people became intrigued by the mystery and volunteered to help and the Carbonne Council came forward with an offer of a 22 tonne excavator (which otherwise the Museum could not have afforded) and its expert operator, Fred Fewings.

In January 1993 a trial dig was performed using the excavator and in just three hours a layer of rock with abundant fish fossils was discovered.

Fossil rock slabs and information boards in the main fossil room of The Museum of Fishes.

In July 1993 Alex Ritchie, Fred Fewings and the excavator dug up the site for eleven days and retrieved a massive 70 tonnes of fossil slabs. The fossils were recovered on about 200 slabs, which contained more than 3,700 fossil specimens, a number of which were of species previously unknown to science. The slabs, some of which weighed 2 tonnes each, were stored in the Canowindra Showground on 100 pallets awaiting the slow process of examination, cleaning, casting and study by scientists and volunteers.

Unfortunately, the exacavation site was in the middle of an important country road (previously known as Gooloogong Road and now known as Fish Fossil Drive) and had to be covered over and the road rebuilt. Hopefully in the future sufficient funds will be raised to pay for a diversion of the country road – so that a full and more detailed excavation of the fossil site's treasures can be undertaken. When that happens new taxa of fish are likely to be discovered.

Why are there so many fish fossils in the one spot in Canowindra?

One of the amazing things about Canowindra fish fossils is that there are more than 3,700 specimens discovered crammed together in a small area. How did this happen?

It is believed that all of these fish were living in pond which suddenly dried out and killed all the fish there in what scientists refer to as a "catastrophic mass-kill event".

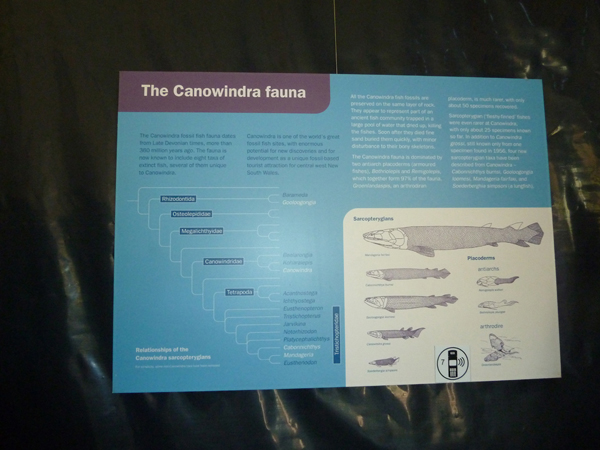

A chronological/hierarchical listing of the Canowindra fauna of past eras.

What species of fish fossils were found?

There have so far been eight species of fossils found. The most important are:

-- two species of antiarch placoderms (armoured fishes), Bothriolepis and Remigolepis - the armoured fishes are by far the most prolific of the fossils found at the Canowindra site.

-- an athrodiran placoderm, Groenlandaspis – 50 specimens found

-- sarcopterygians (lobe-finned fishes), of which four genera have been found (Canowindra, Cabonnichthya, Gooloogongia, Mandageria) and all of these are only known from this site. The species Canowindra grossi is part of this group. These are very rare and only 30 sarcopterygian fossils (approximately) have been found at Canowindra.

Why are the Canowindra fish fossils so important?

There are two reasons.

The first reason is that Canowindra's fish fossils is they are very abundant and that they are extremely well articulated are very well preserved.

-- "Abundant" because more than 3,700 specimens have recovered from the one site (and many more will be recovered when the site is explored further). This is in contrast to the fossil fish site at Buchan, Victoria where the fossil-bearing rock has been mined for many years and as a result a large number of fossils have been destroyed.

-- "Well articulated and well preserved" because we can see that most of the fossil specimens recovered are almost complete in each case, there is little evidence of post-mortem disarticulation (that is, the bones have mostly not not been pulled apart or otherwise disturbed after death by decay, scavenging or predation, and we can see fine detail, even to the extent that we can see the "internal structure of brain cases and gills" (Australia's Fossil Heritage, p. 9). This is in contrast to other fish fossil sites such as Mt Howitt, Victoria where the fossils have not been well-preserved and are often badly weathered.

The second reason is the contribution that the Canowindra fossils, and especially the species Canowindra grossi, have made to the evidence for the theory of evolution.

The original slab found by the road worker back in 1955 is still the most fascinating for in the middle amoung a large mass of fossils of armored fish is a single fossil of the species now known as Canowindra grossi.

This fish was a lobe-finned, air-breathing fish.

(a) Lobes that look like limbs

When we look at the Canowindra grossi's lobes, they look like miniature limbs or legs (rather than just the usual fish fins).

These lobes contain arrangements of bones that look somewhat similar to the bones that we have in the human legs:

-- long bones (similar to our femur, tibia, fibula),

-- followed some small bones (similar to bones in our ankle),

-- followed again by several small bones (that look similar to our phalanges or toes).

This scientists regard the Canowindra grossi's lobes as as rudimentary limbs (legs or arms).

(b) Air-breathing rather than using gills

The Canowindra grossi also breathes air (rather than taking oxygen in from water via its gills as most fish do).

These two special features of the Canowindra grossi -- its rudimentary limbs and its ability to breathe air -- suggest that it is an intermediary species in the progress of the evolution of species between earlier animals (such as fish) and later animals (such as amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals, including humans).

Perhaps the Canowindra grossi could be one of "missing links" long sought for by biologists as support for the theory of evolution.

A big welcome to The Museum of Fishes! This huge black fossil (on display just inside the front door of the Museum) is an example of the Dunkleosteus, a northern hemisphere armoured fish which used to grow to almost 7 meters in length. It just shows how big some of the armoured fishes of the Late Devonian period could grow.

|